What the hypothesis of an effective market is talking about and what it is not talking about.

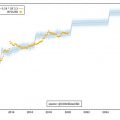

As we approach the third halving,among bitcoiners, debate aboutwhether the reduction in emissions is already included in the price or not. Those who are inclined to doubt the significant effect of halving on the price usually refer to the hypothesis of an effective market. So this concept has become a source of enormous bitterness and controversy for the crypto community. Disagreements often turn out to be insoluble, since skeptics operate on an extremely inaccurate view of the efficient market hypothesis, and as a result, the parties cannot even agree on definitions. Meanwhile, a mutual understanding of the concepts is necessary for a fruitful discussion. Seeing how often people misunderstand this concept, I decided to explain it from scratch, expecting from readers only minimal knowledge in the field of finance.

The origin of the efficient market hypothesis

The authorship of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) is attributed to several scientists, including Benoit Mandelbrot, Louis Bachelier, Friedrich Hayek and Paul Samuelson. Hayek's essay«Use of knowledge in society»sets the necessary basis for understanding the concept,although the GER itself is not mentioned in it. In his work, Hayek speaks out in favor of a distributed market economy, contrasting it with a centrally planned system. The basic idea is that markets are information aggregation mechanisms that no central planner, no matter how skilled or resourceful, can match. Let me quote:

[Even] a moment's thought will show thatundoubtedly there is a mass of very important, but disorganized knowledge that cannot be called scientific (in the sense of knowing universal laws) - this is the knowledge of the special conditions of time and place. It is in this respect that almost any individual has a certain advantage over everyone else, since he possesses unique information that can be advantageously used. However, it can be used only if the decisions depending on this information are provided to the individual himself or worked out with his active participation.

[…] A shipper who makes a livingusing cargo ship voyages that would otherwise remain empty or half-full, or a real estate agent whose knowledge is almost exclusively that of temporary opportunities, orarbitrageur <speculator (fr.)>, playing on differences in local prices of goods - all of them perform highly useful functions, based on special knowledge of fleeting circumstances unknown to other people.

From the fragment in italics you can understandhow Hayek looks at markets: as forces that accumulate many different views and expectations and put them into prices. Hayek understands market prices as information, as a particularly powerful source of information. The beauty of the markets, according to Hayek, is that, simply acting selfishly in accordance with their interests, people participating in the economy create signals in the form of prices. GER directs the same optics precisely to financial assets, based on the fact that investors collectively reflect relevant information that is transmitted to prices through the bidding mechanism.

After a number of studies on stock returns such as«Proof of erratic fluctuations in correctly predicted prices»(Proof that Properly Anticipated PricesFluctuate Randomly, 1965) by Samuelson, EER was finally formulated by legendary financial scientist Eugene Fama (you may have heard of the Fama-French model) in 1970 in a paper (PDF) called Efficient Capital Markets:A Review of Theory and Empirical Work(«Efficient capital markets:review of theory and empirical research) Fama defines an efficient market as one in which «prices always fully reflect available information». Even if you stop here and read no further, you will already have a better understanding of what is meant by efficient markets than the authors of numerous Twitter cartoons. GER is not something mysterious. It is simply a statement that market prices reflect the information available to market participants. This is why scholars often call such markets «information» effective. Efficiency here refers to the dissemination of information.

But what does this mean?This simply means that if new information regarding a traded asset becomes available, that information will typically be quickly reflected in the price of that asset. And if there are any future events that can reasonably be assumed to affect the price of an asset, then, as a rule, this information is included in the price immediately,as soon as it becomes known. Markets do not wait for the predicted events to occur.events - they react proactively. This means that if the weather forecast predicts a hurricane next week that threatens to destroy sugar cane plantations, then speculators, in anticipation of a supply crisis, will increase the price alreadyToday. Of course, there are unpredictable externalshocks (imagine a hurricane crashing into a plantation all of a sudden). In this case, the price can respond to events only in real time, when information about the hurricane becomes known. The speed with which information is embedded in the price is one of the criteria for the effectiveness of markets.

Despite the simplicity of the idea, the hypothesis aboutMarket efficiency tells us a lot about how markets work. Markets are efficient if prices adjust quickly to reflect new information. Forecasted events that can affect the market are usually included in the price in advance. Importantly, one of the consequences of GER is that after all the relevant information is included in the price, only random fluctuations, called “noise,” remain. This means that although asset prices will continue to change even in the absence of new fundamental information, these fluctuations themselves do not convey any information.

And finally, the difficulty of finding a unique newinformation (not yet included in the price), as a rule, depends on the sophistication of market participants and the liquidity of the asset. This explains why you can gain an advantage in stocks of little-known microcapitalization companies, but probably not in predicting the value of Apple shares.

Following Fama's article and thanks to popular books on the subject such as «A Random Walk Down Wall Street» («Random walk aroundWall Street») Burton Malkiel, heated debate has erupted over the advisability of active investment management. Indeed, since the efficient market hypothesis suggests that reliable advantages are so difficult to find, many investors wonder whether actively traded instruments such as mutual funds or hedge funds make any sense at all. Over the past decade, trillions of dollars have been withdrawn from such «active» stock selection strategies and translated into passive investment instruments tied to the performance of the entire market or a specific sector. This is one of the hottest debates in the world of finance today, and is largely due to the growing awareness that markets are generally efficient.

Description of the hypothesis of an effective market

If it were up to me I would call itmodelefficient markets, not a hypothesis.Because it doesn't really contain a hypothesis, but rather a concrete and testable statement about the world. As I wrote above, the EER states that market prices reflect available information (which, as we have already noted, is the main purpose of markets as such). Interestingly, Fama, in his 1970 paper, also calls this an efficient market model, not a hypothesis. His vision seemed to match mine.

In my opinion, the «effective hypothesismarket» It even sounds somewhat tautological. We know from Hayek's work that (free) markets measure a society's net information position with respect to various assets. So, replacing «market prices» on «concentrated information conclusions», we get the following statement:

«Concentrated information findings reflect available information».

It definitely sounds like a tautology. However, the model does not become less useful from this..On the contrary, this means that challenging the GER is everythingis tantamount to questioning the very nature of markets. Indeed, most criticisms of EERs (I will discuss several of them later in this article) tend to cover cases where market equilibrium is not achieved for one reason or another. So if you accept the formulation «efficient market hypothesis» tautological, then «efficient markets» are also starting to sound redundant. (Free) markets should be efficient by default, because that's what we need markets for. Markets reward those who find valuable information that is relevant to them. If they weren't effective by default, we wouldn't spend time or attention on them.

Treating this as a model allows you toclearly understand that this is just an abstraction of the world, a description of how markets should work (and usually work), but not an immutable law. This is just a useful way to think about markets.

I'll say it straight:I don't believe in «strict form» the efficient market hypothesis (its radical interpretation), like none of the financial professionals I know. The strict form states that markets reflectallinformation, all the time.If this were true, there would be no hedge funds or active money managers. No one would bother studying Apple's quarterly reports or assessing the prospects for oil discoveries in the Permian Basin. Given the size of the active wealth management industry, in which many bright and educated professionals are constantly seeking new information about various assets, a strict form of ERM hardly holds water.

Frankly, the efficient market hypothesis isthis is not what you «believe» or not. The choice here is that you either understand markets as useful mechanisms for discovering information, or you reject the usefulness of markets entirely.

Of course, there are conditions in which marketsbecome ineffective. Fama in her 1970 work also acknowledges this, noting that the cost of transactions, the costs of finding relevant information and differences between investors can potentially reduce market efficiency. Here I will focus on two of these factors: the cost of detecting significant information and the barriers to actually expressing views on markets.

If the ERT is generally true, then how are the funds spent on finding information offset?

So what explains the fact of the existence of the wholea large (albeit declining) industry active in investing despite the fact that markets are generally efficient? If market-related information is usually already priced, then there is no benefit in finding new information and trading in accordance with it. However, it is clear that many people and companies are actively trying to discover new information. This looks somewhat paradoxical.

And that brings us to another one of my favorites.articles, «On the Impossibility of Efficient Markets» (English, PDF) («On the Impossibility of Efficient Markets») by Grossman and Stiglitz. The authors point out that collecting information is not free: it also has a cost, and sometimes a high one. They then note that since the EER states that all available information is immediately expressed in prices, the cost of finding new information will not be covered under this model. Therefore, markets cannot be perfectly efficient: there must be information asymmetries that provide compensation for informed traders. Grossman and Stiglitz introduce a useful new variable into the standard market efficiency model: the cost of obtaining information. The model implies that if information becomes more expensive, markets become less efficient, and vice versa. The extent to which markets reflect their fundamentals depends at least in part on the difficulty of finding relevant information.

The authors come to the following conclusion:

We have argued that since information isexpensive, prices cannot fully reflect the available information, because otherwise, those who spent the resources to find it would not have received any compensation. There is a fundamental conflict between the efficiency with which markets disseminate information and the incentives for information.

Grossman and Stiglitz arrive at a rather beautifulconclusion: in order to bring prices back to the level at which this type of activity will be profitable, there must be a cohort of traders constantly knocking prices out of equilibrium. Fisher Black (from the Black–Scholes formula) gives us the answer in an excellent article calledNoise(English noise), published in the Journal of Finance.He identifies a group of unsophisticated traders who make trading decisions based on “noise” rather than information. Noise can be found anywhere. Just go to Tradingview and take a look at the many indicators that people rely on. Black divides market players into two cohorts:

People who trade based on noise are readytrade, although objectively for them it would be better not to do this. Perhaps they take the noise, on the basis of which they make trading decisions, for information. Or maybe they just like to trade.

With a sufficient number of tradersnoise», the market can compensate for the costs of those who have information to trade. Most of the time, the group of noise traders will lose money, while the information traders will make money.

Noise, according to Black, «makes financialmarkets possible». Noise traders provide professional firms such as hedge funds with liquidity and are valuable counterparties against which they can trade. If we draw an analogy with poker, then those who trade on noise are “fish.” They make the game profitable for the sharks, even with the rake (the commission charged by the poker club for each pot). Ask any former poker player - once the environment became more competitive and unsophisticated players left, poker was no longer profitable enough to continue playing.

Noise theory resolves the «apparentimpossibility» efficient markets – Grossman and Stiglitz write about this. The existence of noise created by unsophisticated traders provides sufficient financial incentive for professional players to factor information into prices. So you can thank the suckers who overtrade on BitMEX with exorbitant leverage - they are the ones who compensate other market participants for allocating resources and discovering relevant information.

If the GER is true in general, how do you explain cases where markets do not achieve equal supply and demand?

Another good question. There are many examples in which the possibilities for arbitration were easy to identify, but for some reason the arbitration could not be closed. The best-known example of this is probably the deal that caused the decline in long-term capital management. It was a double deal on bonds that were almost identical, but priced differently by the market (partly due to the 1998 Russian default). Long-term capital managers relied on bond prices converging to a single value. However, many other hedge funds made the same leverage bet, and when bond prices did not meet on time and some fund investors began to withdraw their funds, funds began to receive margin calls and were forced to liquidate these positions. This marked the beginning of the feedback cycle, provoking new liquidations: cheaper bonds were sold, and more expensive instruments continued to grow, as short positions on them were covered. Long-term managers relied on market efficiency and convergence of these instruments, but due to unfavorable market conditions and reduced accumulated leverage, they were unable to complete the transaction, and the fund burst.

This phenomenon is explored in a 1997 paper by Shleifer and Vishny entitled«The Limits of Arbitrage»(«Limitations on Arbitration»).The authors point out that arbitrage is not typically carried out by the market, but rather is a task delegated to specialized institutions (usually funds). Arbitration is an expensive operation that requires free capital. There is a paradox: the best arbitrage opportunities occur when the market is under pressure (for example, when many stocks are trading at low price-to-book ratios). But in times of market stress, capitalleast accessible.Thus, arbitrageurs who need capital to work are the worst offers when they are most needed. This creates restrictions for arbitration. According to the authors:

While arbitration requires free capital,arbitrageurs can become the most limited precisely at those moments when the best opportunities are opened before them, i.e. when the wrong score against which they are betting is further exacerbated. Moreover, the fear of this scenario will make them more cautious when opening their initial positions, and therefore less effective in ensuring market efficiency.

Take a simple example of a value hedge fund,which attracted external capital. They will inform the partners (hedge fund investors) of their intention to play against the crowd - for example, to buy valuable stocks when they are cheaply valued. Suppose the market falls and they buy a basket of stocks with a lower rating and low P / E ratios (price / return). Now imagine that after this the market drops another 40%. Fund investors suffer losses and want to withdraw their funds. This is the worst time possible: the fund is forced to sell shares at a loss, even if the managers are absolutely convinced that they will earn on them in the long term. They would rather buy stocks, the valuation of which has now become even more attractive. But even worse, liquidating positions further increases bearish pressure on stock prices, forcing other funds to make similar deals.

Therefore, Shleifer and Cherries believe that:

Performance based arbitration, especiallyineffective in conditions of market instability, when prices are significantly reduced, and arbitrageurs have already invested all the capital available to them. In these circumstances, arbitrageurs may be forced to leave the market when they most need their participation.

Refinement to the hypothesis of an effective market aboutthe limitations of arbitration can in fact be explained by many situations where people describe market conditions and complain that the information is not reflected in prices. This statement is often perceived as somewhat contrary to the hypothesis of an effective market. But, of course, you cannot expect malfunctioning markets to work properly. Therefore, when the alleged multi-billion capitalization of Dentacoin is presented as an example of market inefficiency, it should be borne in mind that the number of tokens in free circulation was probably scanty, the concentration of ownership was extremely high, and obtaining a loan to open a short position was impossible. This means that market participants are not able to meaningfully express their opinion about the asset.

More complete concept

Given these limitations (featuresmarket structure, cost of information and limitations for arbitration), we can develop a more complete version of the effective market hypothesis, which will include these refinements. A modified GER could sound something like this:

Free markets reflect available information to the extent that pricing entities are willing and able to act in accordance with their information.

- Free markets -because government controlled marketsmay not achieve equilibrium between supply and demand (for example, currency markets with capital restrictions do not provide reliable signals as sales may be effectively constrained).

- Pricing entities -because small players in most cases are not decisive. A small number of participants with significant capital is enough to include significant information in the price.

- To the extent that they are ready to act -this relates primarily to costobtaining information. If the cost of obtaining the information is greater than the benefit of using it (for example, in the case of discovery of accounting mismanagement in micro-cap public companies), then it will not be reflected in the price.

- Have the ability to act -this refers to the emerging restrictions forarbitration. In the event of a liquidity crisis, or if markets for some reason do not function properly and funds are unable to express their view of the situation through market means, markets may become ineffective.

So when most professionals from the fieldfinance talk about GER, they, as a rule, mean a modified, somewhat expanded version of it, similar to the one presented above. And they almost never talk about «strict form» GER.

It is interesting that, only slightly clarifying the GER, we come across a completely alternative concept. The model I have described here is somewhat reminiscent ofAndrew Lo's adaptive market hypothesis.In fact, although I’m happy to claim thatmost (liquid) markets are efficient; in most cases, the adaptive market model much more accurately reflects my views on markets than any of the formulations of the original GER. Many current financial managers that I know are at least familiar with Law's work.

In short, Law attempts to reconcileconclusions from behavioral economics, which reveals obvious irrationality in investor behavior, with orthodox GER. He calls this the adaptive market hypothesis because it takes an evolutionary approach to markets. Developing Black's ideas, Law divides market participants into "types", creating a different, different from the dominant, idea of \u200b\u200bthe efficiency of markets:

The amount of information reflected in prices isdictated by a combination of environmental conditions and the number and nature of the «species» present in the economy, or, to use the appropriate biological term,ecology.

Law describes opportunities to profit from information asymmetries as "resources", which leads the author to formulations such as this:

If many species (or members of oneof numerous types) compete for relatively scarce resources in one market, this market is likely to be highly efficient, such as the market for 10-year US Treasury bonds, which really responds very quickly to the appearance of the most relevant information. On the other hand, if a small number of species compete in the market for fairly abundantly represented resources, this market will be less efficient - such as the Italian renaissance painting market.

The contextualism and pragmatism of Lo's model are consistentwith the experience of most traders who intuitively feel that market participants are quite heterogeneous, and well understand the concept of «table selection» borrowed from poker. I won't go into Law's theory here, but I would highly recommend checking out his book.

What does this mean for bitcoin in the context of halving

As we have already seen, most markets are efficientmost part of time. This is not something that markets do just occasionally; this is their main task. I've already talked about some exceptions: restrictions on arbitrage, captive markets, the influence of some behavioral biases, and situations in which market participants may not be sufficiently motivated to search for relevant information. The question is, do any of these caveats apply to the Bitcoin markets? At the moment it appears not. We are not experiencing a liquidity crisis. There are no visible restrictions on arbitrage. In the era of «pre-financing» (I would say until 2015) one could convincingly talk about such restrictions. In fact, there was no easy way for a high-net-worth entity to express an optimistic view of Bitcoin's prospects. But today there are such ways.

When it comes to freedom, Bitcoin is definitelyis a very free market, one of the freest on Earth (given that the asset itself is extremely portable, easily hidden and traded all over the world). Unlike most currencies, it is not backed or guaranteed by any sovereign, and is not subject to capital controls that might prevent its sale. Market participants can take large short positions in Bitcoin, so they have ample opportunity to express a full range of views. Thus, opposite the column «functioning markets» You can safely check the box. Now, is Bitcoin a large enough asset for a significant number of high-profile funds to make an effort to discover material information related to it? With a market cap of $150 billion, I believe this is absolutely true. A final test of market efficiency is whether market-relevant information is included in the price immediately or with some delay. It would be nice to see research into the price impact of external shocks, such as exchange hacks or sudden regulatory changes.

The only prerequisitesmarket efficiency, for which some questions still remain, are the lack of a common assessment model for market participants, according to which they would measure their decisions, and the development of financial infrastructure. There are still several classes of subjects for which getting bitcoins is quite problematic. Of course, overcoming these problems will make Bitcoin's prospects more rosy.

But as for the halving, is it already included inprice or will it be a catalyst for growth? If you read up to this point, then you must understand how absurd it seems to me that the pricing entities could somehow lose sight of the planned reduction in the rate of issue of coins. Anyone who is at least a little interested in Bitcoin knows about the limitation of the total volume of emissions, and the gradual reduction of output. The total volume of the issue was registered in the first version of the code, which Satoshi published in January 2009. Planned changes in release rates are not new information. Any expected demand side reactions to halving are expected for professional funds that have a strong incentive to play ahead of investors.

But can the price of bitcoin rise from the currentlevels? Of course. I do not believe that the growth of the exchange rate, if it occurs, will be associated with an absolutely predictable change in the rate of emission (reduction from 3.6 to 1.8% in annual terms), but, of course, I believe that there are other factors that can have a positive effect on the price, and most of them are difficult to predict. Is this consistent with the efficient market hypothesis? It is consistent. GER allows for information shocks (imagine, for example, that rampant inflation has occurred in a large world currency). It is also possible that pricing entities take an overly conservative position regarding the future of Bitcoin or act on the basis of a weak fundamental model. This fits into a broader understanding of the ERT.

Regulated securities markets have structuralbarriers to efficiency in the form of prohibitions on insider trading. As Matt Levin likes to say, insider trading is a form of theft: when someone trades on information that doesn't belong to them. Since insider trading is prohibited almost everywhere, pending catalysts such as acquisitions typically do not reflect in stock prices until they are announced. However, in virtual goods markets such as Bitcoin, insider trading standards generally do not apply. If some catastrophic bug is discovered, you can expect the information to be reflected in the price immediately. So in this sense, it is quite possible that the Bitcoin marketmoreinformationally more efficient than, say, the American stock market.

General objections

Next, I will examine some common objections to the efficient market hypothesis. It is likely that here you will find answers to your questions.

I discovered a case of inefficiency. This indicates the inefficiency of the markets as a whole.

It's like throwing a ball into the air andto claim that his temporary separation from the earth disproves gravity. Few practicing finance professionals will argue that all markets remain effective 100% of the time. If the information is distributed unevenly or the information holders do not have enough funds to express their views on the market, then prices may not reflect the information. Brief periods in which markets do not explicitly reflect information are simply an excuse to wonder why market participants were unable to put relevant information into the price. Such cases do not indicate the weakness of the GER, but rather enhance its usefulness as an explanatory tool.

Markets cannot be truly effective due to the irrational behavior of market participants driven by their own biases.

The researchers actually found a numberpersistent behavioral errors, and I think it is likely that they systematically affect asset prices to varying degrees over the medium term. However, the question here is whether they are relevant to the case at hand - the supposed impact of changing the rate of coin issuance on the price of the asset - and how much this supposed irrational behavior can actually affect the price formation of a highly liquid $150 billion asset. You might say: “But there is a common bias among Bitcoiners that encourages asset prices to rise when the rate of issuance drops sharply, even if this information has long been known to everyone.” If you can prove, in the style of Kahneman and Tversky, that this is a universal human perception that influences asset pricing and contradicts dominant market models, then you will not only win the argument, but you will also be in contention for the Nobel Prize. In this situation, I would once again refer you to Law's hypothesis of adaptive markets.

The Bitcoin market cannot be effective, because this asset has no fundamental factors affecting price formation.

Some people believe that cryptocurrencymarkets are driven solely by the emotions of participants, and the fundamental factors for these assets simply do not exist. This is a convenient misconception. Meanwhile, there are quite obvious fundamental factors, with the significance of which, I think, everyone will agree. Here is a short non-exhaustive list:

- The quality of financial infrastructure,providing people with access to bitcoin and allowing them to own it. In 2010, it was almost impossible to buy bitcoins, and the only options for storing them were Bitcoin-QT or a paper wallet of our own manufacture. Today you have access to one billion dollar bitcoins and you can either store them yourself or rely on someone from the world's largest asset managers or custodians. This is a fundamental change.

- Bitcoin software quality (compare the current version with the first Satoshi client). The protocol itself and the software tools around it have been improved, redesigned, and become more useful.

- Actual stability and functionalitysystems - imagine a situation in which Bitcoin could not produce new blocks within a month. Of course, this would affect the price. If you agree with this statement, you acknowledge the existence of fundamental factors, and not just investor sentiment.

- Number of people in the world who know about Bitcoin andcreating demand for it. In the crypto world this is often referred to as «acceptance». And we're not just talking about sentiment here; it is an indicator of which sources of capital are actively seeking exposure to Bitcoin.

There are many other fundamental factors aboutwhich I won’t talk about here. Funds that trade Bitcoin seek to track the trajectories of these variables and find out how overvalued or undervalued Bitcoin is relative to these indicators. This is called «fundamental analysis».

Again, if I have not convinced you, just thinkabout the contrast between the state of Bitcoin in 2010 and 2020. During this time, it has become orders of magnitude easier to buy, sell, use and store. This is a change in fundamental factors. Of course, these are not the fundamental factors that apply to stocks with cash flows, but bitcoin is not a security either. The Bitcoin unit is the right to claim a place in the register that gives you access to the specific transactional functionality of the network. I admit that the fundamental factors here are not as obvious as stocks. But the concept of fundamental factors is not exclusively limited to capital or instruments with cash flows. Global macro-investors consider currencies based on macro variables or an assessment of political risks. Commodity asset traders look at the pace of production and the ups and downs of supply. Here we can draw some analogy.

All this suggests that the funds have significantmarket information on the basis of which they can make their decisions, and not just moods or hype cycles. Just getting an accurate fundamental assessment of Bitcoin is not easy.

The efficiency of the bitcoin market is impossible due to its volatility.

Volatile markets can be efficient.Efficiency implies that the available information should be reflected in the price. Think about the value of a call option with an expiring date and the price of the underlying asset fluctuating around the strike price. One minute the option is “in the money”, and the next minute it’s completely useless. This situation combines volatility and efficiency.

Or another example: the reaction of the price of the Argentinean state. bonds for the political crisis. The fundamental factor here is the desire and willingness of the Argentine government to pay off its debts. Efficiently functioning markets will continually review debt repayment prospects. During a period of change, the main fundamental factor becomes volatile, as, therefore, the value of bonds.

Bitcoin's volatility comes in part fromthat market participants are quickly reconsidering the prospects for its growth, in terms of both pace and trajectory. Even small changes in growth expectations have a significant impact on implied present value. (Indeed, in discounted cash flow stock valuation models, the results are extremely sensitive to long-term growth rates.) Market participants often revise their expectations for growth, and their forecasts vary (because there is no one dominant model for the price of Bitcoin), which leads to increased volatility, especially against the backdrop of inelastic supply. If expectations for future growtharefundamental factor, then the rapid reassessment of these expectations generates constant price volatility. So volatility does not negate or exclude efficiency.

If the GER really worked, then the price of bitcoin would initially have to be at current levels.

It doesn’t work like that. The world is different. As I said above, Bitcoin was not as mature and stable from the first days as it is now. He had to grow to the current grade. In the early period, there was considerable uncertainty as to whether he could even achieve success at least to some extent. Bitcoin had to go through many adversities and trials in order to be where it is now. So, it didn’t make sense to place large funds in Bitcoin from the very first days (although in hindsight, of course, this meaning is quite obvious), because no one had any confidence that it would grow, and because in many cases people just did not have the opportunity to invest in it. Think about how you would acquire Bitcoin in 2012, two years after it appeared. You would have to use something like Charlie Shrem's BitInstant or Mt.Gox (which has gone bankrupt since then), which, as we now know, worked literally on parole. Bitcoins could be mined, but it was a difficult technical task.

And this brings us back to the topic of limits to arbitrage. Many investors, evenwishingbuy bitcoins from 2009 to this day,simply could not do this for regulatory reasons, due to emerging operational risks and due to the lack of a functioning market infrastructure. Even if they were confident that Bitcoin would one day be worth $100 billion, they had no way to express this view through market means. Besides, investors didn't start out with strong convictions. They needed to see how well Bitcoin would perform in real-world conditions before they would decide to invest meaningfully in it. If you agree that the continued success of Bitcoin itself also represents new information coming to the market, then you understand that the EER does not require the asset to appear on the market immediately fully formed and with an initial valuation of more than $100 billion.

What is influenced by the popularity of Ponzi schemes such as Plustoken cannot be effective.

I agree that investors in Plustoken who bought(and then sold) about 200,000 BTC, were an important bitcoin price driver in 2019. But this is not related to efficiency. If in the West it was known that all these coins were at Plustoken, they were about to sell them, and the price of Bitcoin would remain unchanged, then I would agree that there are big questions regarding efficiency. However, information about the Plustoken bitcoins leaked west much later, when most of these coins were already sold out. Remember: efficiency is not about the fact that the price should be fixed; efficiency implies that price must respond to new information.

The market value of small-cap assets soars hundreds of percent on dubious news. This indicates market inefficiency and refutes the GER.

Again: local or temporary evidence of alleged irrationality does not refute the efficient market hypothesis. You either think that markets are good mechanisms for evaluating information or not. Of course, many of these microcapitalized altcoins are structurally poor. They can be traded on unregulated or illiquid exchanges. And this means that the prices you see do not necessarily reflect reality. Thus, episodes of pumping and depreciation of illiquid assets prove little for both points of view, except for the poverty of the market environment in which they are traded.

Generally speaking, most GER proponentsrecognize the presence of a positive correlation between the size of the asset and the professionalism of market participants. It will be very difficult to gain an information advantage in large publicly traded stocks. Most likely, if you find some relevant information about Apple or Microsoft, then someone else will also find it. But in smaller, less liquid asset classes, the return on discovering relevant information is much less, and therefore, analysts who actively put information into the price of assets become smaller, and this increases the likelihood of finding unique information. This is due to the fact that large multi-billion dollar funds simply cannot realize their strategies by trading assets with microcapitalization.

It is easy to conclude that the scale of the market affectsits effectiveness. Bitcoin is not a micro-capitalization token, it is a globally traded asset worth more than $ 100 billion. This provides a high return on finding relevant information and expressing it in the form of transactions. Thus, there is a big difference between inefficient altcoins with microcapitalization (where the income from the detected information is small and the markets are weak) and a mature asset with many analysts seeking informational advantage.

The price of crypto assets with low capitalization does not decrease during 51% attacks or against the background of negative news. This indicates the inefficiency of cryptocurrency markets.

Here I would again refer to Lo (seriously -read about responsive markets!). From the point of view of the adaptive markets hypothesis, this could be explained by the fact that owners of low-capitalization assets are usually supporters of the project or, even better, are in close contact with like-minded members of the founding team. In these conditions, cartel models of behavior may well arise. You could see similar discussions in Reddit and Telegram: coin owners urge each other not to sell them, especially in the absence of bad news, despite the fact that the crypto community briefly paid attention to the project. Buying amid bad news is the way issuers try to mitigate the effects of the negative catalyst. But this can only work in small markets where property has not been widely distributed.

In addition, it is worth considering that practicallyno one owns these assets because they like the underlying technology or find that particular variant of code copied from Bitcoin Core or Ethereum interesting. Microcap crypto assets are held in order to capitalize on a likely future pump. So the problems of the protocol itself are not for these assetsfundamentalfactors.What is fundamental is rather the willingness of the issuing team to ensure "acceptance", or at least the appearance of it, through favorable press releases and partnership agreements. Until the core protocol falls apart completely, the «fundamental» the issuing team's ability to create excitement may remain intact.

Since some bitcoiners mechanically buy BTC on a regular basis (read: pay tithing), and the volume of the new offer will decrease, this will automatically lead to an increase in the rate.

This is an example of level one thinking.GER belongs to the second level. For me, the main idea of the SER is that any information that you have is also available to a professional market participant. Since professional participants have a strong financial incentive to find relevant information, you can bet that they will actively express their views on this information once they discover it. If the hypothesis that static buying pressure from halving the rate of output could have a positive impact on price were plausible, the funds would have long ago expressed this positive vision in the form of a deal. This is called «incorporation into the price». If it is discovered that something significant is going to happen tomorrow, then this information will be included in the price today. This may not be easy to grasp at first.

And the question then is rather not whether«Is this particular information, in a vacuum, a price driver?»The question is, «Do I have information that even the most talented and well-resourced analyst at a large hedge fund does not?« #187; And if the answer to the second question is negative, then we can safely expect that this information is already included in the price (to the extent that this information is significant).

Why am I focusing so much on foundations?Because these are specialized companies that are busy aggressively seeking new information and expressing it in the form of transactions. They are the entities that keep the price in accordance with the «fundamental factors». It is important to remember that no one in the market operates in isolation from the rest of the world. The market is like the digital equivalent of a jungle with predators lurking around every corner. These predators are skilled, fast and well-resourced.

In the context of stock markets under predators, II mean funds whose managers have personal relationships with executives and financial directors - they have dinner with company executives and find out how optimistic they are about the next quarter. Funds in which dozens of analysts operate with sets of such data that you did not even suspect existed. They will track the movements of corporate jets to predict the conclusion of an agreement. They will launch a machine learning model to evaluate Jerome Powell’s emotional state from his eyebrow movements when he announces the actions of the Federal Reserve. They use satellite imagery to gauge congestion in front of supermarkets to see if Walmart’s quarterly performance will exceed forecasted values. Public markets are incredibly competitive. Some of the most talented people make a career on them, and the ability to act on the basis of available information is limited only by a ban on insider trading. Anyone who believes that he has gained an information advantage can freely express his vision with the help of market tools.

So if you believe that you haveMarket-related information (such as the expectation that a reduction in the rate of emission will become a driver of price growth), the most sophisticated market participants also have this information. And they already appreciated the prospects and took appropriate action.

In addition, we must not forget that markets are notdemocratic. They are capital weighted. «Keith» can express his vision much more powerfully than a small fish. Hedge funds simply have much more capital (and typically have access to cheaper leverage). And when they develop a certain position regarding any asset, they have the opportunity to express their vision in the market. This is how information is included in the price. Thus, most of the time, it is the price-determining entities that matter.

Plustoken collected 200 thousand BTC (~ 1% of the totalaffordable offer), and their sale has become an important driver for the price of bitcoin in 2019. Is it not logical to expect a similar effect from halving (affecting 1.8% of the output)?

First of all, the rise and fall of Plustoken was not an expected event. This was truly new information - so much so that most investors only learned about the scale of this ponzi schemeafterhow much of Bitcoin was alreadysold out. Additionally, as far as we can tell, the Plustoken BTC wallets were liquidated in a relatively short period of time: must have been around 1-2 months. This is a large amount of BTC for such a period in any market. The reduction in the rate of production leads to a decrease of 1.8%, but on an annualized basis. This means ~24,800 less BTC will be mined each month. This is a fairly large number, but not at all the same as 200,000 BTC being liquidated in a short time. And unlike the Plustoken sale, this reduction is known in advance.

Halving will increase demand for bitcoin, inspiring investors and through media coverage. Due to this, halving will in any case be a positive catalyst for the price of bitcoin.

The same logic works here as in the answer above. Using the example of Litecoin, you can clearly see how the price rose sharply in anticipation of a halving, and then plummeted immediately after the event itself. It is likely that just in this case, investors hoped for halving as a positive catalyst. Here you can see how investor assumptions about the behavior of other investors affect the price. You find yourself in a recursive game where everyone watches everyone and everyone tries to predict how the others will behave. Thus, even if there is a lot of pressure on the demand side by the halving date - due to press coverage or just the anticipation of investors - this will not come as a surprise to pricing organizations and will probably already be included in the price months before.

If markets are efficient, then investing in Bitcoin is pointless.

It's not like that at all.Some informational aspects of Bitcoin - such as the emission schedule - are completely known and transparent. However, as I already mentioned, many of the fundamental drivers of Bitcoin's price are not easy to analyze or even easy to detect. For example, no one knows the real number of Bitcoin holders in the world. If you can predict such factors more accurately than others, you will gain a certain advantage. Additionally, there are many likely unpredictable shocks - such as currency crises - that could have a positive impact on Bitcoin's prospects. Critics of the GER often overlook the fact that it only provides for the expression by marketsaffordableinformation. Obviously, the currently unknown future catalysts are not included in the available information. They haven't happened yet.

After all, if you predict growthBitcoin is more accurate and better than other pricing entities, then you can use your excellent understanding to make a profit. And I think this is a plausible prospect. So I do not completely exclude the possibility that bitcoin can be attractive to an active financial manager, even taking into account the GER. I myself am very optimistic about the future of Bitcoin. And, of course, I believe that specialized knowledge in the field of Bitcoin can be of great value. If I were a supporter of the strict form of GER, I would not be engaged in active asset management. In fact, active managers are almost most interested in finding ways to completely abandon GER. And the fact that I am giving arguments in support of it already speaks volumes.

As an example of how a demand-oriented fundamental model for Bitcoin might look, I can offer you a translation of an interesting article by Byrne Hobart.

With a moderate form of GER, fundamental analysisquite possible and even necessary. In the end, someone has to analyze the data and find information that will ultimately be laid down in the price. This work has been left to the active financial manager. So maybe these nasty hedge funds and their managers also have some benefit.

</p>