At first glance, many aspects of proof-of-stake seem simple and intuitive, but they are misunderstoodeven those who have devoted a good deal of their livesthe study of crypto assets. This has led to an incredible amount of misinformation in this area, with large twitter accounts in pursuit of the attention of the brainless masses making a fool of themselves in front of anyone who has even a rudimentary understanding of the second-order effects of staking. In this article, the author of the DataAlways mailing list hopes to clear up a few common misconceptions about this and maybe encourage the reader to think about what else they may be misunderstanding.

Many people naively believe that all usersPoS blockchains should be as interested in staking as possible, apparently inspired by high staking rates in L1 alts. But if you look, the situation is much more complicated.

At the individual level, the choice of whether to takewhether or not staking is involved can be approximated as a simple balance between return, risk, lack of liquidity, and convenience. (Though this is just one way to approximate dynamics; I'm sure there are more complex and better ways to model it.)

Adjusted_Yield = Yield × (1 — Discount_Risk) — Liquidity_Premium — Convenience

In abbreviation:

A = Y × (1 — D) — L— C

- A: adjusted yieldstaking - the profitability receivedvalidator after adjusting for other variables. If the adjusted staking return is positive, then the optimal choice for an ETH holder would be to lock them up for staking.

- Y: staking yield— average expected return per validator forexpected staking period. For the initial, genesis, stakers, the profitability could initially be more than 10%, but taking into account the blocking of tokens for several years, the average profitability over the period could be about 6%. (From a fixed income perspective, it would be more accurate to measure this as expected cash flows during the staking period.)

- D: risk discount— direct modifier of staking profitability,taking into account validator downtime, possible reward slashing, technical risk of unsuccessful merge, etc. It can also be used to factor pool and/or exchange fees into calculations, but I prefer to think of third-party staking as a form of DeFi rather than staking itself.

- L: liquidity premium- represents opportunity costs,related to participation in staking. For example, if your coins are locked for staking, then you will not be able to use the same ETH to trade NFTs, nor will you be able to instantly transfer or sell those funds if the need arises.

- C: convenience modifier, i.e.I wouldn't go through the long process of setting up a node if the expected return on investment is 0.1% per annum. Personally, I need at least a couple of percent per annum to have some incentive to do it myself. (The convenience modifier could theoretically be negative if the person is such an altruist.)

- It may be appropriate to include in C the cost of running a home validator. Or you can add another cost variable to the formula.

In theory, every holder of Ethereum shouldmake a similar rough estimate and find your adjusted staking yield to determine if it is positive or negative and by how much. With a positive adjusted return, staking can make sense, with a negative one, obviously, the risks and disadvantages outweigh the benefits, and staking becomes unjustified.

Given this methodology, it's no surprise that liquid staking derivatives (LSD - from Liquid Staking Derivatives, not what you might think) have become so popular:

- The validators are operated by generally reliable operators, which reduces the risky discount.

- LSD allows you to get out of stake beforewithdrawals will be officially allowed, perhaps at less than face value, but still better than being stuck with coins staking indefinitely.

- LSDs increase liquidity as you can quickly exit via Curve instead of waiting in line for the validator.

- LSD is more convenient because you don't have to manage the validators yourself.

- As compensation, liquidity providersstaking take some percentage of the return, but for most holders, such derivatives are an effective tool for extracting returns.

By rearranging the above formula, we can determine whether the adjusted staking return is positive using the inequality:

Y × (1 — D) > L+C

As a result of this rearrangement, the question of whetherwhether it makes sense to participate in staking becomes a question of whether the return on staking, discounted for risk, exceeds the opportunity cost of staking and the effort required to run a validator.

When people from traditionalfinance and start talking about staking as a risk-free rate or "internet bonds", they often don't take into account the risk factors associated with staking. Here's a more accurate representation:

RFR = Y × (1 — D)

With the introduction of the risk-free rate,division between financial speculators and technologists. From a financial perspective, in order to maximize the dollar value of ETH, a compelling strategy is to set a high risk-free rate to attract as many tokens as possible into the staking contract and create a supply shortage. This line of thought leads to price models based on discounted cash flow projections (DCFs) or similar, in which analysts model staking returns as company returns, assuming that higher returns should push the price of the token higher.

An under-discussed consequence of thisis that a high risk-free rate makes it nearly impossible for anything else to compete. If you have a risk-free rate of 10%, then everything else: DeFi, NFT, blockchain gaming, etc. should either generate yield or grow in price at a rate that outpaces this rate (plus a spread to compensate for additional risk). A high risk-free rate simply leads to long-term stagnation of the ecosystem.

Two important takeaways for non-speculators:

- Low staking returns are better than high returns in terms of ecosystem sustainability (see also this post by the author).

- A high staking ratio is a sign that something is wrong with the blockchain.

- Polynya suggests that the preferred staking ratio could be 10% (assuming sufficient network security).

Comparison between staking ETH with formInternet bonds has an additional nuance: when you buy a bond, you get a short yield because you are rate-pegged, unless it's a floating rate bond, but normally the floating rate on bonds is designed to keep the spread constant as the underlying changes, such as like LIBOR or federal funds. In contrast, when staking ETH, the holder is left with a long yield. And I want to remind you that staking returns are inflated right now and will certainly fall in the coming months, so being in a long yield is not ideal.

Staking ETH also comes with huge risks,if you do not hedge changes in the spot price. In this sense, staking ETH is similar to foreign bonds with high currency risk, which most large money managers will need to hedge by shorting spot or futures.

EIP-1559

Burning transaction fees is the brightestan example of a misunderstood update. Often criticized as financial engineering to drive up the price of tokens, in a proof-of-stake environment, EIP-1559 lowers the risk-free rate and makes it easier for dApps to compete with staking.

The main narrative around EIP-1559 has always beena deflationary offer, but for infinite holders (who must gravitate toward staking to ensure no depreciation) burning tokens is actually a negative!

A mental model that can help thisto be clear, is to think of burning tokens not as a reduction in supply, but distribution of it among all holders of ETH. From this point of view, transaction fees that would normally only go to stakers are returned to all members of the community - when implemented with a proof-of-stake blockchain, EIP-1559 is actually a decentralizing mechanism, and not centralizing, as many opponents claim.

The main criticism of EIP-1559 comes down tomainly to the fact that it is a form of pro-cyclical monetary policy. In an episode of the On The Brink podcast, Nick Carter noted that the correlation between token price and activity results in fewer tokens being burned during a bear market and more during a bull market. This creates a feedback loop, which in theory should result in higher highs but less pronounced lows.

One of the main problems with reasoning aboutThe first and second order effects in cryptoassets is that we have so many correlated and inversely correlated measures that it is very easy to make inaccurate extrapolations. In this context, the gas market may not control the price of a crypto asset, but the use of the network: lowering the price of gas will reduce token burning, but lowering the price of gas will help stimulate network use. This effect is similar to how the Fed prints money during a recession: theoretically, each unit in circulation becomes less valuable, but with more money, the economy can recover faster than with tough Austrian-school policies.

Meanwhile, the decline in income from stakers due toburning transaction fees (instead of paying them to stakers) also keeps returns low, further spurring network activity.

In private messages on Twitter Nick Carter later(without prompting) revisited his "pro-cyclical" comment and acknowledged the complexity of the relationship between price and network activity, noting that there are both pro-cyclical and counter-cyclical aspects of network renewal. And I agree with his more nuanced stance, which could hardly be properly articulated when recording a podcast.

Real and nominal staking returns

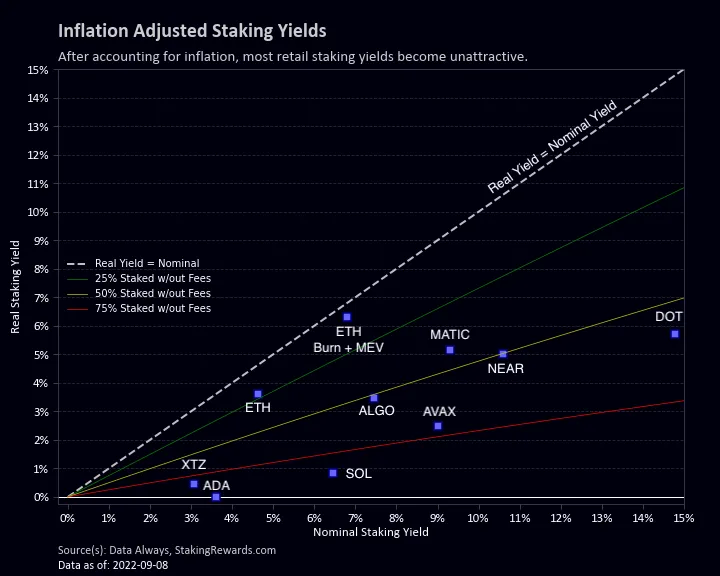

In the last few months, the context of the discussionreal staking returns, as well as completely vague estimates, have expanded significantly, with particular focus on farming returns. However, many L1 altcoins continue to show high staking returns but only offer small inflation-adjusted returns due to high staking ratios (percentage of coins staked).

In the chart below we see that mostThe largest proof-of-stake blockchains offer virtually no return for staking their tokens. For example, delegating tokens to Cardano is often seen as an easy way to generate almost 4% returns, but after adjusting for devaluation and fees, the returns actually become negative. This is a ridiculous situation: with a negative real return, you are expected to also pay taxes onearnedyou tokens.

The main thing to remember:

If there is no one left from whom you can extract income, then no one will receive income.

Staking returns, framed as a tax on liquidity, only have value if there are those who are willing to receive liquidity.

With Ethereum, the situation is much better now, but duringThis is largely due to low staking rates and token burning. With the stabilization of the transition to proof-of-stake and the inclusion of the option to withdraw tokens from staking (risk reduction), the staking coefficient will increase, reducing its real profitability.

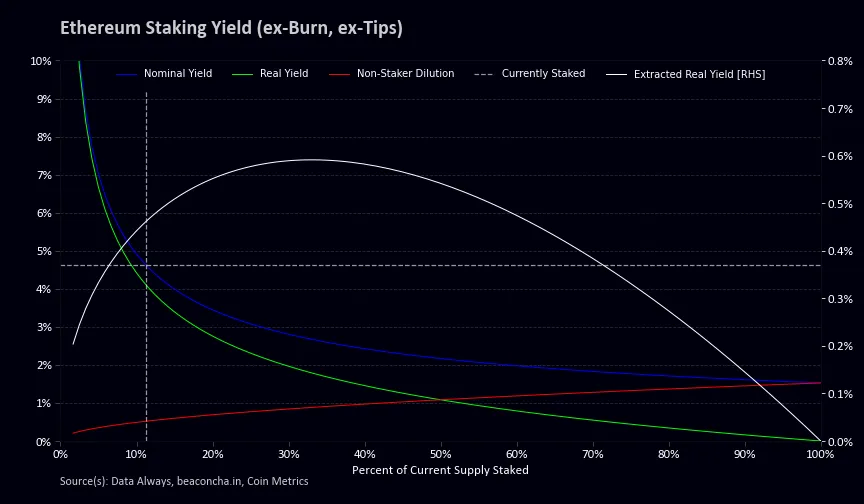

Digging deeper into the Ethereum yield structure, wewe can plot a naive yield chart without MEV and token burns to establish a floor for yield and a depreciation cap. The chart below shows that while the nominal return remains above 2% as long as less than 60% of the tokens are staked, the real return falls below this mark as soon as the staking ratio reaches 30%; if 60% of the Ether is staking, then the underlying real yield will fall below 1%.

Such high staking odds are simply notare good dynamics for the network. Locking tokens while taking on the risks of slashing and liquidity for a 1% profit is not an efficient state for a blockchain that claims to be the “world computer”. The only people who will be happy with such returns should be infinite-horizon speculators who want to keep their market share but have no interest in using the network.

One can also define diminishing returns fromstaking by calculating the total real yield extracted by the validators. When the number of validators exceeds 30% of the total ETH supply, the profit generated will begin to shrink and any additions of new validators will begin to resemble pure inflation rather than yield extraction. In essence, the reduction in reward from more staking ETH outweighs the increase in overall real return from an additional validator. In fact, it’s even more profitable for the validator pool to pay the additional validator its potential staking income so that it doesn’t get involved in staking.

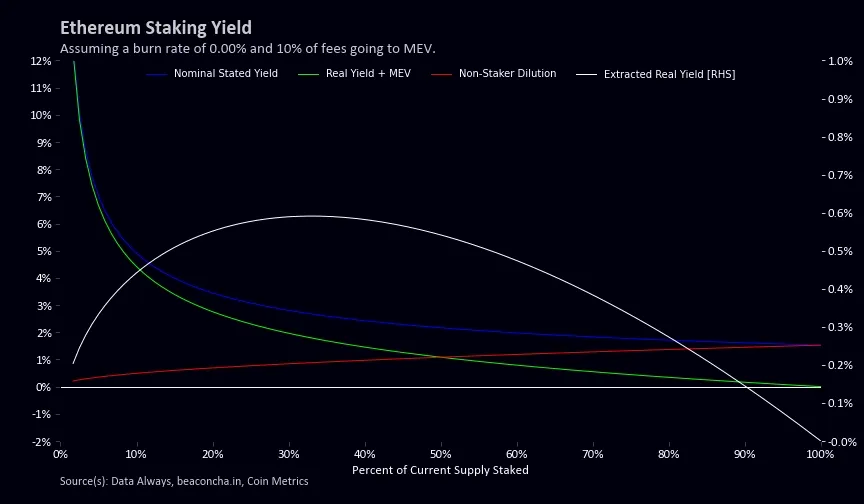

Extracted Real Return = Real Return × Staking Ratio

In a more realistic model that takes into account combustiontokens and MEV at current gas prices, but with a staking ratio of 30%, real returns are astonishingly low: only about 3%. Most of today's discounted cash flow or yield models that point to an 8% return are only relevant in the near-short term as long as the number of stakers stays at the 10% level. And they won't be later on unless we return to a high fee environment where higher staking ratios provide meaningful real returns, but most of that returns come from burning tokens, which non-stakers would also benefit from.

As for extracting real returns, thenafter accounting for MEV, stakers face the same maximum recovery barrier at a staking ratio of around 30-35%. The MEV could push this boundary even lower, as a higher staking ratio implies less actively traded Ether, which drives down the price of gas.

Note:many in the community expect that the switch to proof-of-stake will create a large demand for the use of Ethereum, which can lead to more on-chain activity, higher burn rates and MEVs. None of my models have ever relied on or attempted to characterize demand growth since The Merge.

Burning while plotting the real curveyield was not taken into account, since its inclusion would lead to the fact that the dependence would increase linearly with increasing percentage of supply in staking. This would be misleading since non-stakers alsoextractthis deflation of supply from the network. Of greater interest is the relative recovery compared to non-stackers rather than the absolute value.

Subtlety, which is worth paying attention to andwhich, at first glance, contradicts my Proof-of-Stake article and the Cantillon effect, which encourages widespread staking, is that it is important not that everyone participates in staking, but that everyone has the opportunity to do so. If the blockchain provides real utility, then it is hoped that alternatives available for staking can generate enough returns to keep staking from reaching 70% or 80% of the tokens locked up indefinitely.

Fetishization of the non-use of a crypto asset, whether it bedecentralized virtual machine or p2p e-cash system is the height of the pursuit of financial performance, not utility, which will ultimately lead to stagnation and death of the communities that strive for it. High staking returns encourage retrieval chasing and should be avoided in my opinion.

Ironically, a popular trend among bitcoinersconvincing people to never spend their coins goes well with proof-of-stake: any staker, by definition, retains its market share, which will not dilute, so proof-of-stake allows a cryptocurrency store of value to instantly lock in a share without worrying about future issuance or potential endgame instability that could lead to changes in monetary policy.

BitNews disclaim responsibility for anyinvestment recommendations that may be contained in this article. All the opinions expressed express exclusively the personal opinions of the author and the respondents. Any actions related to investments and trading on crypto markets involve the risk of losing the invested funds. Based on the data provided, you make investment decisions in a balanced, responsible manner and at your own risk.

</p>