In simple words about the activities of central banks.Bank of England. European Central Bank. Federalbackup system. Bank of Japan.You've probably heard these names if you have had any interest in financial news in the last ten years. The image that can be imagined at the same time is men in suits sitting at a round table and discussing boring issues.

These are approximately the pictures my imagination could offer.

"So let them eat the cakes!"

One photo is a frame from Hunger Games 2, the other is a business breakfast of the ECB Governing Council. (Guess where what?)

Like the world after the 2007-2008 financial crisis,The Hunger Games is a post-apocalyptic dystopia in which neighborhoods fight to the death to maintain control. However, today we are not talking about emotional conclusions and vivid metaphors, but about how to tell in simple words about central banks. So let's get down to it.

What are central banks doing?

In a nutshell, central banks control the money supply in the economy. For example, the European Central Bank controls the money supply of the eurozone economy, which consists of 19 countries.

Many people just don't know what they are doing.central banks - in large part because it seems like a rather boring topic, unless you are somehow involved in the financial markets. This can be quite difficult to understand. But the role of central banks in the economy is vital, as their targets and the decisions taken to achieve them have different impacts both on the economy and directly on your pocket.

Generally, central banks have three goals:

- price stability;

- full-time;

- preventing inflation (and deflation).

Price stability is related to how muchcurrency becomes more expensive or depreciated, and is also closely related to the last target on the list. If the exchange rate falls sharply against other currencies, it can have inflationary consequences. On the other hand, if the currency becomes more expensive, it can lead to deflationary effects in the economy.

Why is that?

This is partly due to what is called aggregate demand. The mathematics behind this term is:

Aggregate demand = consumption + investment + government spending + (exports — imports)

The rise in the exchange rate makes imports cheaper, but the aggregate demand may decrease at the same time - this factor must be taken into account. (And the opposite is true if the exchange rate falls.)

Purposefully manipulate the exchange ratecentral banks don't usually try. However, they focus on an inflation target based on the consumer price index (CPI). And in my opinion, this approach has many disadvantages.

Central banks look at the CPI as a barometerprice stability while ignoring asset prices, which may have a much more negative distributional effect on people's spending. For example, house prices skyrocket when interest rates are low.

Why?

If the interest rate goes down, bank loans become cheaper.

Central banks assume that the correctthe policy to stimulate the economy during a downturn is to lower interest rates and increase liquidity in the economy by increasing the availability of bank loans and facilitating the flow of credit funds. This is achieved through so-called quantitative easing, one of the tools available to them in open market operations that they use to try to rebuild the economy.

I have already written about problems with quantitativemitigation in this article. Central banks believe that by increasing or decreasing the volume of credit in the economy, they can influence the CPI inflation - to increase or decrease the level of prices for goods included in the consumer basket. In the article I just mentioned, I explain why there are clearly problems with this premise.

Central bank governors assumethat inflation should be kept within the target range of 1-3% (formally measured at +/- 2%). But when a means becomes an end, it ceases to be a good means!

Let's take a look at what central banks are likely to be looking at when justifying their rate cut decisions.

This is a supply and demand diagram showing the relationship between economic goods and liquidity preferences.

IS = Interest-savings

LM = Leveraged Market.

It is assumed that with an increase in the money supply, interest rates will fall and the national income will rise. While this may be the case, at some point it starts to create problems.

When we get close to the par rate of zeropercent (also called the zero limit), we find that the previous options for the influence of central banks have been exhausted. They are then forced to take advantage of broader opportunities (such as quantitative easing) as consumers fall into a so-called liquidity trap.

Because of low interest rates, people accumulate cash as savings rather than buying bonds in the hope that interest rates will rise soon.

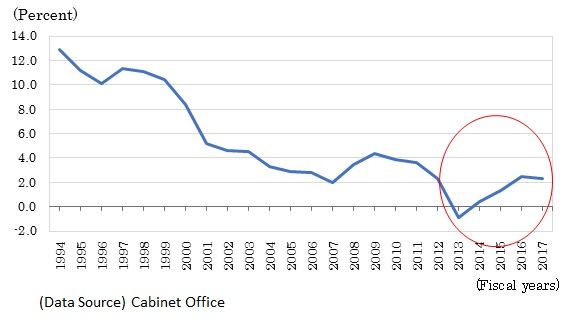

The personal savings rate in Japan mirrors this mechanic in action.

In Japan, the interest rate remainednegative since 2016, while inflation also remained stagnant. This is despite the fact that the Bank of Japan has dramatically increased the money supply and has used even more unconventional methods than other central banks in an attempt to increase inflation in order to be able to raise the interest rate and return the situation closer to normal.

An example of their more than unconventional methodsThe increase in the market for leveraged funds is the purchase of ETFs traded in the domestic market, in which they are by far the largest owner with a share of more than 80%.

Another aspect that central banks don't acceptinto account - this is how the consumer will react to the rise in asset prices due to the "cheapening" of borrowing. If the cost of buying or renting a home rises, then the ability of consumers to spend money in the economy will diminish, which will curb inflation.

Why low interest rates are bad

Together with this, another problem arises:low interest rates reduce productivity. When it is so easy to get capital at low (and even negative) interest rates - especially in Europe - we are actually just feeding what should really be dead.

In Europe, companies are less likely to gofor financing to the capital markets than in the US. Instead, they go to banks. And banks make money by issuing loans. If they can provide loans to solvent companies, then who cares that these companies are not really able to improve anything? Banks make money.

The problem is that salaries are not going up.And the net benefit to the economy as a whole is likely to be very small, apart from preventing the inevitable - as in the case of unforeseen extreme shocks such as the coronavirus pandemic.

According to S&P forecast, the level of corporatedefaults in Europe this year should rise from 3.5% to 8.5%. Alexandra Dimitrievich, chief research officer at S&P Global, believes that given the record number of companies receiving downgrade warnings - 37% of companies and 30% of banks - and the decline in the quality of loans issued, the rate of defaults will increase:

“A third of speculative grade companies in Europe are rated B- or below, which is 10 percentage points higher than before the pandemic. That is why we expect the number of defaults to almost double. "

The consequence of low rates is the systemnegative selection of those in whose favor it makes sense to distribute capital. And this creates a kind of vicious circle in which garbage companies continue to exist and discourage the allocation of capital to innovative enterprises that could actually contribute to economic growth.

Back to what central banks are doing

Let's take the US Federal Reserve System as an example, as it is the most important central bank in the world. How do they actually make decisions?

There are twelve voting members:seven from the Fed's Board of Governors and five from other Federal Reserve banks. The President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York always has a seat on the council, while the other four voting seats are won by one president from the group and replaced annually. There are four groups in total: Boston, Philadelphia and Richmond; Cleveland and Chicago; Atlanta, St. Louis and Dallas; Minneapolis, Kansas City and San Francisco. The link above can be used to see the current composition of the committee.

By law, the Federal Reserve Committee on Operations on the Openmarket (FOMC) should meet at least four times a year, but since the global financial crisis in 2008, this happens about twice as often in order to better monitor and adjust monetary policy.

Voting members invite a friendtheir forecasts and, in fact, decide at what level to set the federal funds rate, the target range of interest that banks charge each other on short-term loans. After agreeing on the decision (some members can vote against, but the decision is made by a simple majority), they send an order to the New York Bureau of the Fed to conduct an agreed operation on the open market, which includes buying and selling securities to achieve the desired goal.

The Fed is implementing a dual mandate:maintaining price stability and controlling unemployment (as described above, but as a rule, they do not explicitly intervene in the foreign exchange market, as a number of other central banks do). This dual mandate is followed by other long-term goals. In particular, this is the revised statement of the Fed (eng., PDF) regarding their long-term strategy.

And on this statement from there, I would like to dwell for a while:

"The committee seeks to clarify its decisions on monetary policy to the public as clearly as possible."

If that were the case, I wouldn't have a reasonwrite this article! The mechanism, which they say should be well understood by the public, is definitely incomprehensible to them. Central banks are clearly not doing this part of their job. And instead of admitting this and changing their useless politicians, they (at best) write meaningless pseudo-academic articles like this one (English, PDF).

Obviously central banks have no ideahow to communicate with the general public. The main problems of their approach, in my opinion, are as follows: 1) the subject of the message (monetary policy) is boring, 2) the representatives are extremely weak in communication with the public, and 3) no one believes either the message or these representatives.

Or is it just a smokescreen and in fact, central banks are completely satisfied with the level of (mis) understanding of their monetary policy in society?

“It’s good that people don’t understand our banking and monetary system, otherwise, I think, the revolution would have happened before tomorrow morning,”- Henry Ford.

But the decisions of central banks are the mostdirectly affect the level of our well-being - in most cases much more significant than the widely replicated general political changes and legislative initiatives.

How do central banks increase the money supply?

Above, I mentioned that the New York Bureau of the Fed conducts operations on the open market. What exactly does this mean?

Well, in order to increase the money supply, you mustbe a mechanism through which the Fed can channel the money it creates into the economy, right? They do this through the purchase of Treasury bonds from primary dealers (commercial banks), which provides them with liquidity to issue loans and conduct business in accordance with the needs of the consumer. Excess cash can also be used. They do this until they reach the target range for federal funds.

The problem is that this mechanism tends toprovoke the subsidence of funds in financial assets, instead of fueling the real economy. The popular phrase that “stocks only go up” is a consequence of this very effect.

The New York Fed's trading department may do the opposite. To raise the federal funds rate, they sell Treasury bonds on the open market, thus reducing liquidity.

Since the federal funds rate rangeis the key rate, it affects all other rates on loans and credits. Therefore, this is such an important indicator for financial markets. And since the dollar is the main world currency (I talked about its importance in this article), any analysis and trading ideas, as a rule, begin with the Fed's policy and the behavior of the US dollar.

All central banks are equal, but some are more equal

Here I built my story mainly onthe example of the FRS, because in the new world after the global financial crisis of 2008, almost all central banks pursue the same goals by approximately the same methods, and the FRS is the main institution, followed by global market participants.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize once again thatin most cases, it is these institutions that primarily affect your well-being. Not the government. And society as a whole clearly needs to pay more attention to the actions of central banks and understanding how their decisions affect (most often with a minus sign) the interests of ordinary people.

</p>