Yield Curve Control: The Next Saga in the Global Monetary Policy Experiment infiat systems. From the US implementation in 1942 to the recent Japanese experiment, what is the essence of yield curve control tactics and what are their consequences?

The key theme of our long-term thesis aboutBitcoin is an ongoing failure of the centralized monetary policy of central banks in a world where such policies are not likely to fix, but only exacerbate, serious systemic problems. The bankruptcies, the pent-up energy of pent-up volatility, and the economic disruption that will follow from central bank efforts to address these problems will only further fuel mistrust in financial and economic institutions. And this opens the way for an alternative system. We believe that such a system, or at least a significant part of it, can become Bitcoin.

With the goal of ensuring a stable, sustainable, and sound global monetary system, central banks face one of the biggest challenges in their history: resolving the global sovereign debt crisis.In response, we will see monetary and fiscal policy experiments unfold around the world to try to keep the current system afloat.One such experiment is known as Yield Curve Control (YCC, fromYield Curve Control) and is becoming increasingly important for our future.In this article, I will talk about what YYC is, a few historical examples, and the future consequences of the spread of this practice.

Historical Examples of Implementing Yield Curve Control

In a nutshell, YCC is central banks' method of controlling and influencing interest rates and the total cost of capital.In practice, the central bank sets its ideal interest rate for a particular debt instrument in the market.And in order to maintain the right interest rate peg, they continue to buy or sell thatA debt instrument (e.g., a 10-year bond) regardless of other circumstances.As a rule, purchases are made at the expense of newly "printed" currency, increasing the pressure of monetary inflation.

Yield curve control tactics can beadopted for several reasons: to maintain low and stable interest rates to stimulate new economic growth; maintain low and stable interest rates to reduce borrowing and debt service costs; or intentionally create inflation in a deflationary environment (to name just a few examples). The success of this policy depends only on the degree of confidence in the central bank in the market. Markets need to be confident that central banks will continue to pursue these policies at all costs.

The largest example of YCC implementation occurred inUSA in 1942, against the backdrop of World War II. The United States incurred huge debt spending to finance the war, and the Fed capped yields to keep borrowing costs low and stable. During this time, the Fed capped short-term and long-term interest rates on short-term bills at 0.375% and on long-term bonds to 2.5%. In doing so, the Fed gave up control of its balance sheet and money supply, which were sacrificed for the purpose of maintaining lower interest rates. It was the chosen method of dealing with the unsustainable skyrocketing public debt relative to gross domestic product.

The ratio of public debt to US GDP

However, by 1947 inflation exceeded 17% (according toyear-on-year consumer price index) and the Fed grew increasingly concerned about the impact of YCC on inflationary pressures, so they stopped using YCC on short-term bills. In 1951, inflation soared again to over 21% per annum, and then the YCC on long-term bonds was discontinued, despite strong opposition from the presidential administration and those in charge of fiscal policy. In fact, it was the Fed who fought to end the YCC, emphasizing:

“Given rising inflation, the FOMC strongly believes that continuing this peg will lead to excessive inflation.”

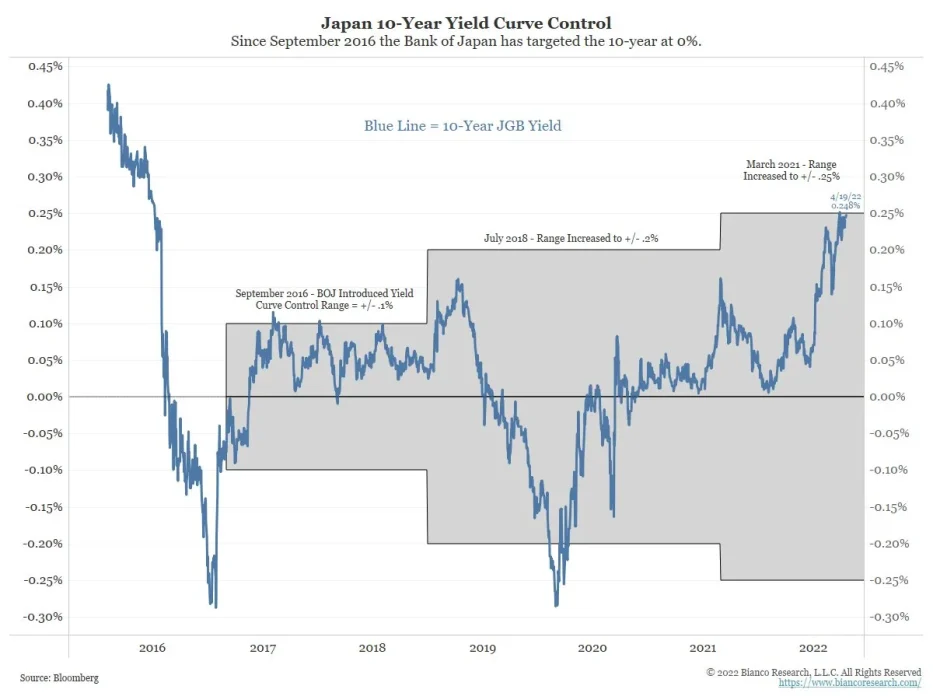

Fast forward to today:in 2016 and 2020, YCC returned to the fore as a heavily used instrument in Japan and Australia, respectively. Over the years, Japan has maintained short-term and 10-year rates at various levels in an attempt to boost inflation to ~2%. And only in April of this year, against the backdrop of a sharp increase in inflationary pressures around the world, Japan was able to raise core inflation above 2%.

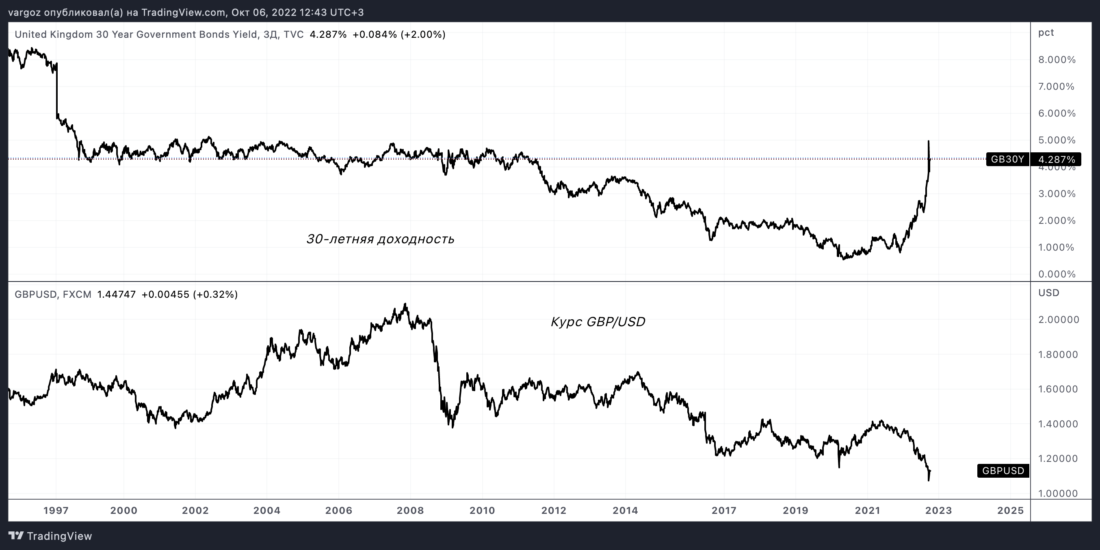

This year, Japan has faced a seriousYCC's choice to keep the policy: let yields rise or the yen fall. Increasing yields is not an option as Japan has the world's largest public debt-to-GDP ratio (around 260%) and faces a multi-decade challenge to spur sustained economic growth and inflation.

Currency devaluation is the other sidea double-edged sword, albeit with a stable YCC policy. As a result, the yen now resembles an emerging market currency, down 20% year to date. By now the situation has gone too far, and the Bank of Japan has moved to full-scale foreign exchange intervention to limit the depreciation, even if this will only provide temporary relief. Losing the yen's value may help import competitiveness and economic growth, but too much of a decline will destroy domestic purchasing power. It appears that we are dealing with yet another example of central banks finding that their policies are more like flipping an on/off switch indiscriminately. and to a much lesser extent on a proven long-term strategy.

:Bianco Research

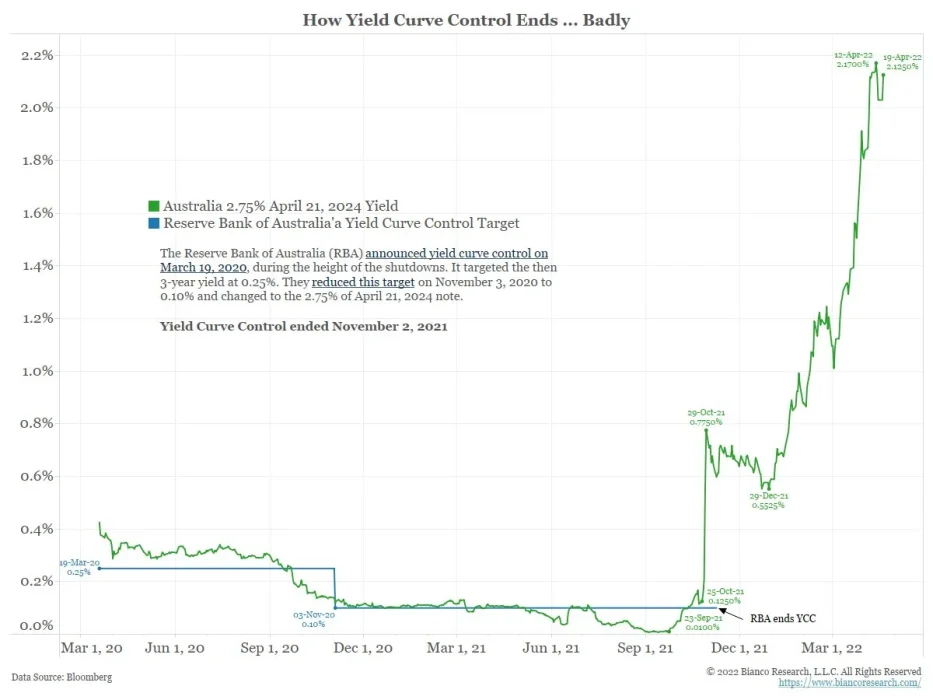

In the midst of a pandemic, Australia set a limitinterest on 3-year bonds at 0.1% in an attempt to stimulate the economy and reassure its citizens that interest rates will remain low and stable through 2024. But amid rising inflation, bond markets caught on to this bluff, pushing rates up to 0.8% and forcing the Reserve Bank of Australia to abandon the program. All in all, the YCC attempt was by all accounts a failure as the Bank of Australia had no real exit plan in place to stop the policy when rates began to rise.

:Bianco Research

The Present and Future of Yield Curve Control Tactics

In addition to these clear examples of the use of tacticsYCC, the European Central Bank (ECB) is actually pursuing a similar policy, but under a different flag. The ECB is buying up bonds to try to control the yield gap between the strongest and weakest economies in the eurozone.

This bond buying turned into something thatnow called the anti-fragmentation tool. The policy is aimed at buying and selling various bonds in EU countries to try to limit yields in the hope of stopping a sovereign debt crisis or preventing a massive default. The spread between Italian and German debt is one of the best examples of why the ECB is worried and feels compelled to resort to drastic measures.

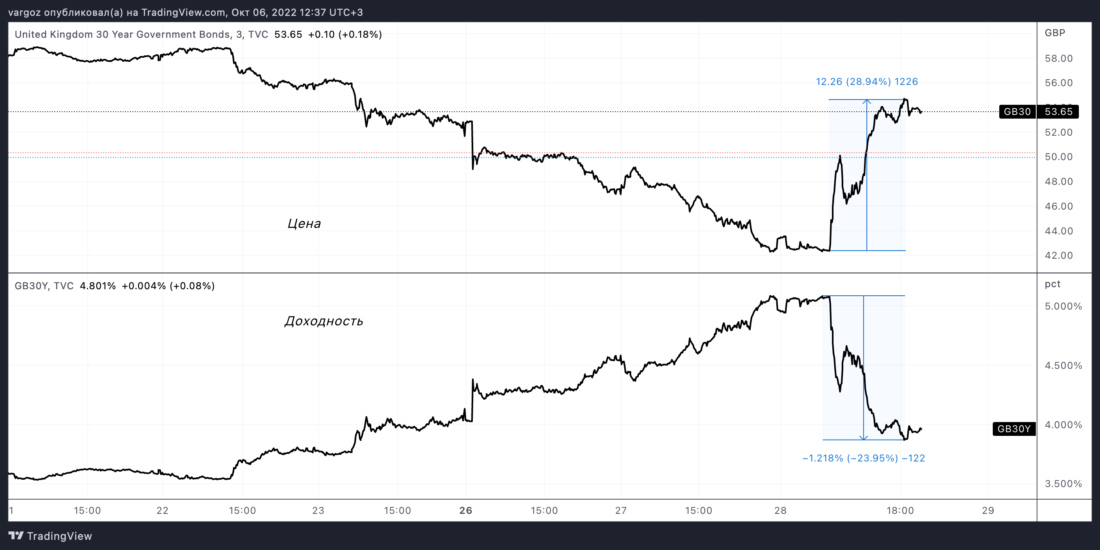

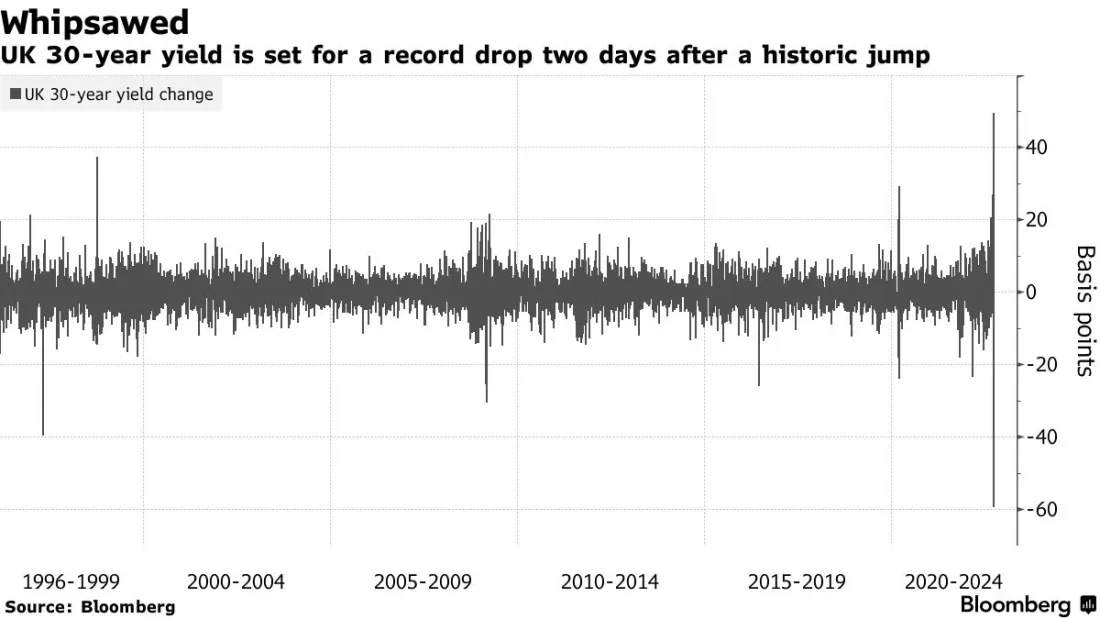

Just last week the Bank of England announcedtaking measures to resume pseudo-«quantitative easing» amid concerns about insolvency risk and margin calls for large pension funds as yields continue to rise. UK 10-year yields stood at 1% at the start of the year and peaked at 4.58% before reversing on news of the new policy. Thirty-year yields hit 5.12% before falling sharply following the Bank of England's intervention announcement. The move - one of the biggest in global bond markets - saw the price of 30-year debt rise by as much as 28.57% in about four hours.

Yields went too high too fastfor the economy to function, and the bond market is now short of margin buyers, with sovereign bonds posting their worst-ever year-to-date performance. This leaves the Bank of England no choice but to act as the buyer of last resort. If the resumption of quantitative easing and initial bond purchases are not enough, then we could easily see a move to a more stringent and longer-term YCC yield capping program.

According to the Bank of England itself, purchasesbonds will continue to the extent necessary, which of course sounds a lot like the formation of a new yield curve control regime. This is reminiscent of Mario Draghi's statement about «whatever it takes» during the European debt crisis of 2009.

«To achieve this goal, from September 28, the Bankwill make temporary purchases of long-term UK government bonds. The purpose of these purchases will be to restore favorable market conditions. Purchases will be made on the scale necessary to achieve this result. The operation will be fully compensated by the Ministry of Finance.

:Bloomberg

It later became known that the Bank of England had intervenedinto a situation to stop the bond movement due to the potential for margin calls in the UK pension system, which holds about £1.5 trillion in assets, most of which was invested in bonds. Because some pension funds hedged their volatility risk with bond derivatives managed by so-called liability-driven investment (LDI) funds. With the sharp fall in prices of long-term UK sovereign bonds, the risk of margin calls on derivatives backed by these bonds as collateral increased. The specifics are not that important here, but the main thing to understand is that when monetary tightening has become potentially systemic,the central bank intervened.

Returning to the intervention itself, the initialthe scale of this operation is relatively small and is not a direct sign of tomorrow's global turnaround. Inflationary pressure is still enemy number one, especially in the UK, where inflation is forecast to reach 9.5% through 2023. The volatility of the British pound is also growing: since the beginning of the year it has fallen by more than 20%. Surely every country experiencing energy import problems and high inflationary pressures is watching Japan's YCC efforts and its exchange rate as a warning sign of how things could get worse.

While yield curve control tactics canto limit the damage from the crisis in the short term, it leads to a number of consequences and second-order effects that will have to be dealt with.

First, rising inflationary pressuresthat could arise from the YCC is difficult to predict even in the more deflationary world we find ourselves in today. With inflation rampant and policy aimed at suppressing it, an increase in the YCC could easily lead us into a world where there are more inflation shocks, not less.

YCC is essentially the end of any remnants of the «free market» in financial and economic systems.This means more active centralizedplanning to maintain a certain value of capital on which the entire economy operates. This is done out of the need to keep the system from a complete collapse, which has so far been inevitable in fiat monetary systems near the end of their expiration date.

YCC policy prolongs the existence of the sovereign debt bubble by allowing governments to lower the overall interest rateon interest payments and reduce the costloans for future debt extensions. Given the size of the national debt, the pace of future budget deficits, and the significant social spending promised far into the future, interest rate costs will continue to take a growing share of tax revenue from a shrinking and under pressure tax base.

As we have seen in manymonetary policies of the past decade, governments continue to increase their share of global debt markets, crowding out private investment. What will be the incentive for private investors to purchase sovereign debt if yields and profits are limited? It is likely that investors will end up holding government debt only because they are forced to adhere to various regulatory and capital controls.

Finally

First Use of Yield Curve Controlwas a global measure of wartime. This tactic was used in extreme circumstances. So even the mere act of trying to deploy YCC or a similar program is a warning signal to most that something is seriously wrong. Now the world's two largest central banks (and a third on the way) have moved to actively pursue a policy of controlling the yield curve. This is a new stage in the evolution of monetary policy and monetary experiments. Central banks will try their best to stabilize economic conditions, and the result will be an even greater depreciation of the money supply.

If ever there was a marketingcampaign explaining why Bitcoin has a place in the world, then this is it. While we believe that the current macroeconomic factors take time to play out and that a decline in the price of bitcoin is a likely short-term outcome in a scenario of severe stock market volatility, the wave of monetary policy and liquidity that would have to be released to save the system would be enormous. Trying to get a lower price to build bitcoin position and avoid another potential wave of drawdown in a global recession looks like a good play (if the market allows it), but missing out on the next big move up is going to be huge in our view missed opportunity.

BitNews disclaim responsibility for anyinvestment recommendations that may be contained in this article. All the opinions expressed express exclusively the personal opinions of the author and the respondents. Any actions related to investments and trading on crypto markets involve the risk of losing the invested funds. Based on the data provided, you make investment decisions in a balanced, responsible manner and at your own risk.